A Case for Christian Universalism

This post was originally written as a critical reading response to The Evangelical Universalist: The Biblical Hope That God’s Love Will Save Us All (2008) by Gregory MacDonald on February 22, 2023, as part of my degree requirements in TH 502 at Kairos University.

The Evangelical Universalist by Gregory MacDonald is a thoughtful, Scripture-based evaluation of universalism - that is, the belief that God will save all people as opposed to traditional doctrines of hell (primarily redemption for the elect/saved and eternal conscious torment for the damned).

Hopeful Dogmatic Christian Universalism

MacDonald describes himself as a “hopeful dogmatic universalist,” which means that he believes with certainty that God will save all but he approaches his universalist theology humbly, stating that “all theological systems need to be offered with a degree of humility, and one that departs significantly from mainstream Christian tradition calls for even more.” (1)

He tactfully approaches the topic first from an examination of the philosophical problems of traditional teachings on hell, then moves toward outlining the biblical support for “a grand theological narrative with a universalist ending,” (2) before making sense of some of the ‘hell texts’ in Revelation and the Gospel of Matthew from a universalist perspective.

Fundamentally, he does not deny the existence of hell, only the eternal existence of hell; instead, he posits that hell exists as divine punishment that seeks to rehabilitate people so that they might wholeheartedly choose God and thus be saved. He also takes pains to assert that he is not pluralist or relativist in his thinking, stating that “salvation is found in Christ alone;” (3) therefore, he makes the case for a distinctly Christian Universalism.

This book was a truly pleasurable read. It was thoughtful, logical, and well-saturated in Scripture, leaving no doubt as to MacDonald’s most sincere intentions in his articulation of a Christian Universalist theology.

Philosophical Problems with Eternal Conscious Torment

In his chapter on the philosophical problems of eternal conscious torment in hell, he outlines the difficulties of the concepts of the justice of infinite retribution (4) and the joy of the redeemed (5).

I appreciate his tackling of the philosophical problems of hell prior to delving into Scripture and biblical theology. His responses to these problems are 1) that justice of infinite retribution seems incompatible with a biblical theology “according to which in the coming age God destroys sin from his creation,” (6) and 2) how can God’s people rejoice in the death of the wicked when God himself does not rejoice? The traditional doctrine of eternal conscious torment thus creates a philosophical and moral conundrum that appears to be at odds with the character of God described in Scripture.

The Logical Problem of Calvinism and Hell

Then MacDonald boldly tackles the issue of Calvinism and hell. Calvinism states that a strong view of divine providence and God’s sovereignty necessarily dictates that God will save whom he will (the elect) and the rest be damned; the believer must trust in God’s ultimate goodness and holiness in his judgment.

However, MacDonald uses reason and logic to dismantle the Calvinist’s claims, stating that “a strong view of divine providence, combined with the claim that God loves and desires to save all people, leads to a convincing argument for universalism” (7) rather than salvation only for the elect. “God, according to the Calvinist, does not love all people and want to save them. If he did then he would. Rather, he loves the elect - his chosen people. It is them he loves, was for them he died, and it is they he will save.” (8)

Thus, MacDonald finds the Calvinist stance that God only loves the elect incompatible with a biblical theology of a God who loves all. He is bewildered by the Calvinist’s emphasis on God’s divine justice in saving only the elect, stating that “justice is no impediment to God’s saving everyone.” (9) In fact, subordinating divine love to divine justice so that God has to be just but does not have to love is simply incompatible with the Scriptures - and the Christian - which confess that God is love. (10)

Universalism and Free Will

A final note on the philosophical arguments addresses the problem of free will and universalism: If God will save all, then do people truly have free will? MacDonald examines the objections of the Freewill Theists who defend a traditional doctrine of hell (11) as well as Open Theism (12) and Molinism (13).

Without reiterating his entire dissection, I will suffice it to say that MacDonald lands on fully informed free will as an explanation for Christian universalism. That is, can anyone who is adequately and fully informed about the gospel reject it freely?

If a person understands fully the depth of God’s love and goodness through the work of the Holy Spirit, can they truly reject him?

MacDonald asserts that the choice to reject God is entirely irrational; the only rational choice left to the person who has absolutely seen God’s grace and holiness as well as the depths of their own brokenness is to choose salvation in Jesus Christ. In regard to hell, he says, “if God respects the freedom of those in hell and permits them to experience the full reality of their freely chosen condition, they will learn the true meaning of separation and will in the end choose to embrace him.” (14)

Thus, he also argues that death is not the ‘point of no return’ and that salvation may be found in the very depths of hell by God’s grace. The conundrum of free will is the most head-scratching philosophical problem that is presented by universalism. However, I find his arguments compelling and they certainly provide a different framework for thinking about life, death, judgment, and most enduringly, God’s love.

What Does the Bible Say About Universalism?

Leaving behind the philosophical, MacDonald then dives into the biblical narrative and biblical theology. He suggests that “any claim that universalism (or traditionalism) is biblical must show how it fits in with the broader picture of Scripture and makes sense of the broader themes.” (15)

He also argues that universalism does not directly conflict with what is explicitly taught in the Bible, particularly biblical doctrines such as salvation by grace through faith in Christ’s atoning work as well as individual texts on hell, therefore universalism is worth examining as an alternative to traditional doctrines of hell. (16)

Firstly, he discusses the theology of Paul’s teaching to the Colossians on Christ, the church, and the cosmos. (17) There he emphasizes that Paul teaches that all things are reconciled to him by the blood of the cross. Then he elaborates on the metanarrative of creation, fall, and redemption, stating that the ‘end goal’ is always reconciliation and redemption, not suffering and death. The story of Easter ends with resurrection, not crucifixion; in the same manner, he argues that the universalist approach ends with redemption, not eternal suffering. As Christ was resurrected, all of creation is also redeemed at the end of time - why should this not also include all of fallen humanity?

“It is God’s covenant purpose that his world will one day be reconciled to Christ.” (18)

Thus, Christian universalism does not take a light view of sin. Instead, it fully acknowledges the depth of the fallenness of creation and the need for redemption through Christ’s work on the cross and his resurrection. It also does not eliminate the need for evangelism; the Church is living in the ‘already but not yet’ of a realized eschatology in Christ, therefore the “Church must live by gospel standards and proclaim its gospel message so that the world will come to share in the saving work of Christ.” (19)

Universalism in the Entire Biblical Narrative

A final point by which I learned much from MacDonald is in the Scriptural relation between Israel and the nations in the Old Testament and Christ’s relation to both in the New Testament.

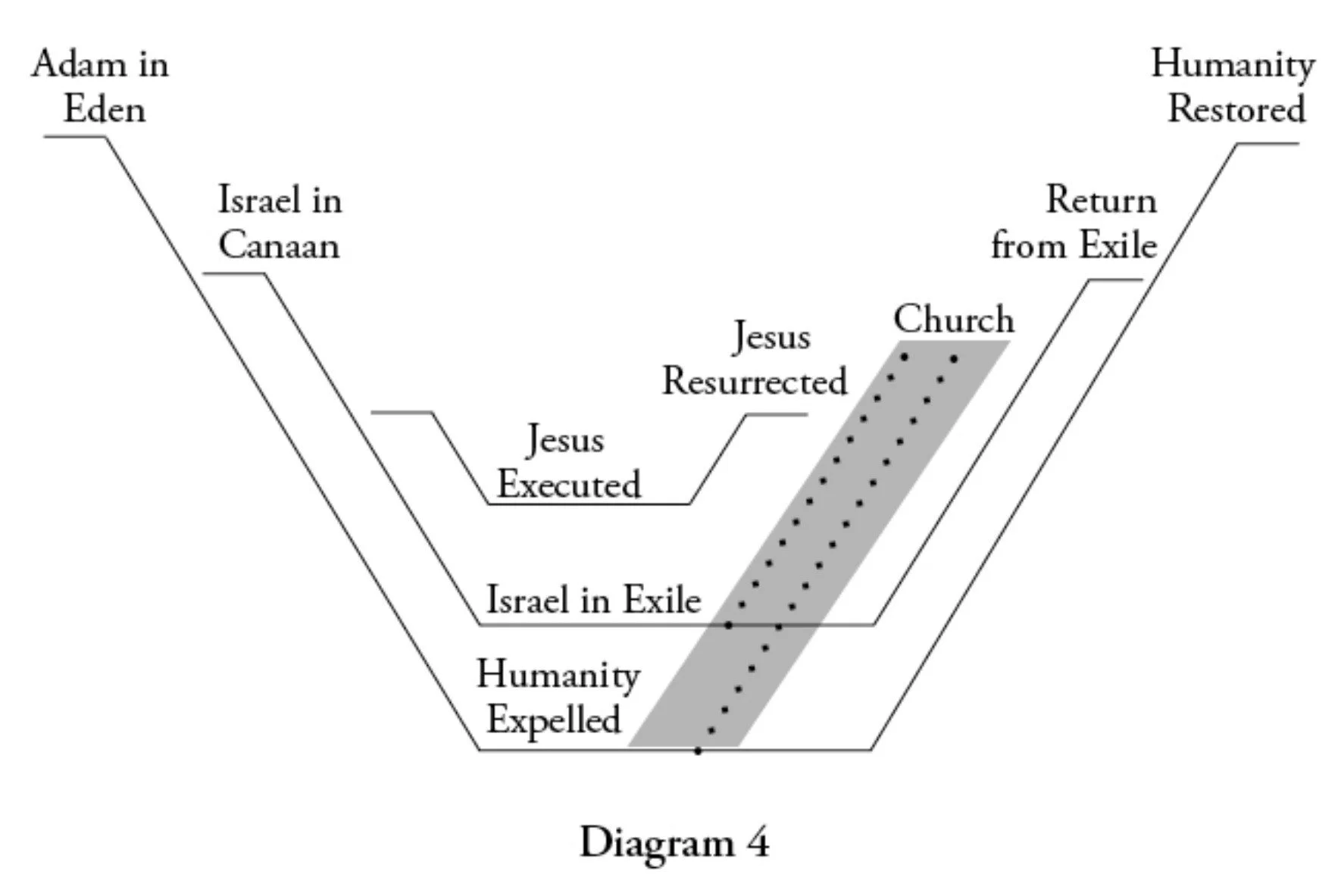

MacDonald explores God’s relationship with Adam and Eve in the garden and his mandate that they are to rule over creation. Then he describes God’s covenant promise to Abram, particularly that “all peoples on earth will be blessed through you.” (20) In a fascinating illustration, MacDonald compares Adam and Eve in the garden with Yahweh to Israel in Canaan; just as Adam and Eve were to fill the land and subdue the animals, Israel was also to fill the land and subdue their enemies. (21) But then, just as Adam and Eve disobeyed God’s commands and were expelled from the garden, so too did Israel disobey God’s covenant and were expelled from Canaan into captivity and exile.

However, all is not lost. “Humanity, in Adam, lost the blessing; but Israel, in Abraham, is the vehicle through which God restores it.” (22) MacDonald takes this parallel a step further in Isaiah’s descriptions of the Suffering Servant: “The Servant embodies in his own story Israel’s exilic suffering and restoration in the imagery of death and resurrection.” (23)

This restoration is not limited to Israel, however. The story of the nations parallels Israel’s story; divine judgment (destruction of the nations) is followed by divine mercy (healing of the nations). (24) Israel’s task is to mediate this divine mercy to the nations, in accordance with God’s promise to Abraham.

Finally, Christ as the fulfillment of the Servant foreshadows the restoration and resurrection of all peoples and all nations. Gentile believers are ‘grafted into the tree’ of Israel and Israel’s task to bring God’s love and mercy to the nations becomes the Church’s task. As Paul wrote to the Philippians, “At the name of Jesus every knee should bow and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.” (25) This is the image of the universal Lordship of Christ and the task of the Church is to bring glory to him by declaring him to the nations. (26)

My Assessment of The Evangelical Universalist

It is difficult to choose a chapter of this book that was most significant to me. I found MacDonald’s philosophical arguments fascinating, and I loved the depth of his chapters on universalism and biblical theology through Israel and the nations, and Christ and the church. His presentation of the topic is reasonable and logical but also firmly rooted in the biblical narrative in a way that I find altogether compelling. Any arguments or rebuttals that I posited in my mind were anticipated and answered in detail.

Whether one agrees with MacDonald’s conclusions or not, it cannot be denied that this book is thorough and presents a humble yet well-supported and well-researched argument for Christian universalism. I have an immense appreciation for how he did not ignore the philosophical implications of universalism, nor did he shy away from analyzing the biblical proof texts so often used in supporting a traditional doctrine of eternal conscious torment. He boldly places universalism within the biblical narrative - indeed, all the way to creation and God’s covenant with Abram and Israel. I appreciate how he does not hang his entire argument on a couple of proof texts but takes pains to place it within the larger story of Scripture. There are those who will find fault with his approach, particularly with his emphasis on reason in the philosophical chapters.

However, I found MacDonald’s approach refreshing compared to many who simply appeal to the ‘mystery of God’ without attempting to explain why we Christians believe what we do.

Simply, MacDonald’s explanation of Christian universalism makes sense to me and fits within my understanding of biblical theology up to this point. It takes into consideration a coherent theology of creation, the Trinity, atonement, salvation, ecclesiology, and eschatology that fits within the broader biblical narrative. None of what he presented is contrary to a truly Christian theology.

In response to those who argue that universalists undermine the severity of sin, he says, “What makes us universalists is not that we have unusually weak views of sin but unusually strong views of divine love and grace. Where sin abounds grace abounds all the more.” (26)

In response to whether universalism undermines evangelism, he says, “The Church embodies in itself God’s mission to the world… Christian universalists share with non-universalists many of their motivations for gospel proclamation: to obey Christ’s command, to save people from the coming wrath, to bring them into living fellowship with the triune God and his church.” (28)

And lastly, in response to universalism and the problem of evil, he says, “God knows how to defeat evil by weaving it into many good and creative plots. Ultimately it is only in relationship with God that horrendous evil is overcome.” (29)

A Disagreement with MacDonald About Jesus’ Teachings on Hell

The only point with which I found myself really disagreeing with MacDonald was his insistence that Jesus’ teachings on hell in the Gospels were specifically about post-mortem judgment. I tend to agree with N.T. Wright on this topic - that much of the apocalyptic language of the Gospels has been misunderstood and refers to actual events within history such as the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70. (30) In this interpretation, none of the Gospel texts may be appropriately used in an argument for or against the existence or state of hell.

However, I will concede that MacDonald approaches these texts humbly as he takes the more traditional approach in interpreting these texts as referring to a literal hell. He never denies the existence of hell or that Jesus taught about hell; he only refutes that hell is a place of eternal conscious torment.

The entire conversation of hell and universalism is a difficult one - not because of how MacDonald presents the material, but because a shift to universalism necessarily shifts one’s entire worldview and interpretation of Scripture. There is a subtle shift in theology from a God of justice and wrath to a God of love who is just and wrathful in order to redeem his people.

However, as I mentioned earlier, I found his arguments altogether refreshing as they align with where I find myself theologically and in my understanding of the biblical narrative. Far from being heretical, I find that Christian universalism is more integrated with a biblical theology of redemption and restoration.

If I could ask the author anything, it might be to ask him how his shift in eschatology has impacted his own life and ministry. He alludes to his journey in the introduction of the book and I would love to learn how long this journey took him and how it impacted his relationships with others.

Why Does a Theology of Christian Universalism Matter?

For myself, I see how this understanding of God’s universal love impacts how I preach and teach Bible study and how I embody the love of Christ in my ethics and work. I do not emphasize God’s wrathful judgment or fear of it, though I do not shy away from teaching the severity of sin (as we’ve seen, sin leads to exile from God which is a terrible thing).

But always the emphasis is on a relationship with God, who is eternally gracious, loving, and merciful. His grace endures even beyond death. As Paul says in his letter to the Romans, “Neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor any other created thing will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (31)

Notes

Gregory MacDonald, The Evangelical Universalist: The Biblical Hope that God Will Save All, (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2006), 14.

MacDonald, 17.

MacDonald, 16.

That is, the punishment of a criminal is on the grounds that the criminal deserves it. The more severe the crime, the more severe the punishment.

That is, the redeemed are in eschatological bliss while the damned are tormented in hell, which poses a severe moral dilemma for those who are saved. Do they forget their family members who are being tormented in hell? How can they be in bliss while there are many who are being tormented at the same time?

MacDonald, 26.

MacDonald, 31, italics added for emphasis.

MacDonald, 31-32.

MacDonald, 34.

MacDonald, 34. See also 1 John 4:18.

Freewill Theists assert that God wants all people to choose him freely, so he will not force his salvation on anyone; see MacDonald, 37.

Open Deism says that God has won the victory so long as he has given all people the opportunity to accept salvation freely and saving those who do accept it; see MacDonald, 38.

Molinism says that God’s “middle knowledge” allows him to know what any person would freely choose if they were in any possible situation which required a free choice, not unlike many descriptions of God’s foreknowledge; see MacDonald, 38-39.

MacDonald, 44.

MacDonald, 56.

Keep in mind that MacDonald is merely arguing that hell is temporary suffering with the express purpose of the individual returning to God rather than eternal conscious torment.

Colossians 1:15-20

MacDonald, 77.

MacDonald, 77.

Genesis 12:3

MacDonald, 85.

MacDonald, 85.

MacDonald, 94.

See Isaiah 19:18-25, 45:20-25, Psalm 72:8-11.

Philippians 2:12

See Appendix A for MacDonald’s visual illustration of the parallels between Adam, Israel, Christ, and the church in reference to redemption and restoration for all; MacDonald, 146.

MacDonald, 229.

MacDonald, 233.

MacDonald, 223.

MacDonald, 197.

Romans 8:38-39, italics added for emphasis.

Appendix A